City needs ‘room to breathe,’ architect says

Kim Sung-woo’s project at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale calls for a thoughtful approach to the Sewoon Sangga redevelopment plans

By Shim Woo-hyunPublished : May 21, 2019 - 18:00

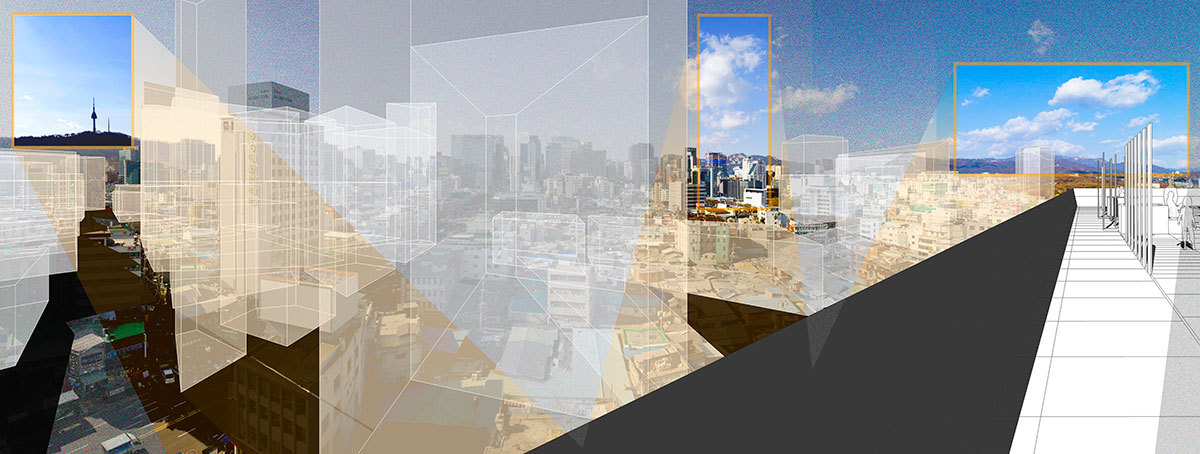

The rooftop of the Sewoon Sangga, the 50-plus-year-old shopping complex in central Seoul, offers a unique panorama of Seoul.

From the northern side of this mega-structure you get a view that spans from the mountain Bugaksan to the Confucian shrine Jongmyo. There is also a clear view of Namsan Tower from the southern side.

The western side offers a skyline that connects Euljiro 1-ga with the gates Gwanghwamun and Namdaemun, while clusters of low-rise traditional markets can be seen to the east.

From the northern side of this mega-structure you get a view that spans from the mountain Bugaksan to the Confucian shrine Jongmyo. There is also a clear view of Namsan Tower from the southern side.

The western side offers a skyline that connects Euljiro 1-ga with the gates Gwanghwamun and Namdaemun, while clusters of low-rise traditional markets can be seen to the east.

But these views could all be gone sooner or later if the site is not properly redeveloped, said architect Kim Sung-woo, voicing the need to preserve what some view as one of Seoul’s landmarks.

At the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018 -- within the Korean Pavilion, titled “Spectres of the State Avant-garde” -- Kim presented his research project “The City of Radical Shift,” in which he looked into the history of the structure and issues surrounding its redevelopment.

“This is perhaps the last chance that the Sewoon Sangga offers us, and we should not blow it,” Kim said of the imminent development pressures imposed on the area.

The Sewoon Sangga and the neighborhood around it are remnants of Seoul’s rapid postwar development.

The Sewoon Sangga construction project was proposed by the Korea Engineering Consultants Corporation -- led by acclaimed artist Kim Swoo-geun -- and the arcade was built in 1967. At the time, the postwar structure was to be a landmark for the eight zones around it -- an area spanning from Jongmyo to Namsan. It was supposed to be a catalyst for the transformation of the city center into a thriving place.

At first, Sewoon Sangga and the nearby Euljiro area were surrounded by tens of thousands of small industrial and electronics shops. But expectations for the neighborhood were soon dashed.

Development projects planned for the blocks around the complex were delayed with the departure of the tenants of its residential units, located on the upper floors, following the development boom in the Gangnam area in southern Seoul. It also took a drastic hit after the development of the Yongsan Electronics Market in 1987, when many electronics shops relocated.

The region subsequently deteriorated, and the aging buildings became eyesores -- yet also potentially lucrative spaces that many wanted to redevelop.

But it was a big challenge to initiate a large-scale construction project as there were simply too many owners to reach an agreement.

“The Sewoon Sangga, which was supposed to boost development in the region, ironically became a sort of safeguard that limited development for the last 50 years,” Kim said.

The complexity of the symbiotic network of numerous urban industrial agents in and around the complex was a major factor in holding development back, Kim added.

Discussions about the redevelopment of the region have continued to this day, having gained momentum in the early 2000s when the Seoul Metropolitan Government initiated the 2003 Cheonggye Stream restoration project.

In 2009, the Hyundai Sangga, the first building in the Sewoon Sangga complex, was torn down. A master plan was conceived to redevelop the neighborhood, but the plan lost momentum when the global financial crisis hit.

It was in 2014 that the redevelopment discussion gained new impetus. That year, the government revised the plan to preserve the Sewoon Sangga and to split the nearby eight sections into 171 units for redevelopment. The sections quickly attracted investors.

Kim said the development process should be approached very carefully as there is no going back. Since the government has decided to preserve the Sewoon Sangga, redevelopment plans have to be consistent with that aim.

“The Seoul government has to come up with restriction measures for the area around the Sewoon Sangga. Once done, it is irrevocable,” Kim said.

Kim’s project calls for an alternative development strategy.

In his project, Kim proposes that planners ensure a good view of different areas of the city from the rooftop of the Sewoon Sangga complex, saying the arcade could easily be trapped within a mass of high-rise buildings if they fail to control private-sector development.

Local governments here can turn down redevelopment proposals if they negatively affect the look of a neighborhood, or if they obstruct the view of another property owner.

Kim also suggested a floor area ratio of 650 percent for the redeveloped space. (The floor area ratio refers to the ratio of a building’s total floor area to the area of the land on which it is built.) That generous figure would give the neighborhood “room to breathe,” he said. Kim added that the Dutch design firm KCAP used a 650 percent floor area ratio in its redevelopment plan for Zone 4 of the area, which city planners judged successful both in terms of feasibility and harmony with the scenic beauty of the nearby heritage site Jongmyo.

“Even if the redevelopment takes place, it has to consider the network of the city, how it is connected. The zone 5-1 makes up the most important area because it works as a bridgehead that connects nearby commercial areas to the Dongdaemun area. If high-rise buildings cover up the zone, it will disrupt the flow,” Kim said.

But the Seoul government is running out of time, Kim says.

In January this year, it decided to put off the development process for Zone 3 for another year. It said it would reassess the overall redevelopment and possibly come up with urban plans that would satisfy both goals: development and preservation.

“The government only has seven months left, but it’s still too short,” architect Kim said. “Yes, it is important to minimize losses to existing business owners in the region. But at the same time, the government has to spend time to come up with a philosophy and detailed alternatives that will guide development in other zones down the road.”

Protecting the aging buildings and infrastructure just for the sake of preserving them is meaningless, according to the architect. He said the area needs to be turned into a place that is sustainable, a place people will actually want to visit. New resources are needed in combination with proper redevelopment plans to reinvigorate the site, he continued.

Kim’s work is currently on display at the homecoming exhibition of The Korean Pavilion, which focused on an archive of four key state projects developed by the government-established Korea Engineering Consultants Corp. during Korea’s industrialization and modernization phase in the 1960s. It also introduces seven research-based artworks by artists and architects.

The exhibition runs through May 26 at the Arko Art Center in Jongno, central Seoul.

By Shim Woo-hyun (ws@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)