Dark secrets of the man who opened architecture to the light

By Korea HeraldPublished : July 21, 2016 - 14:35

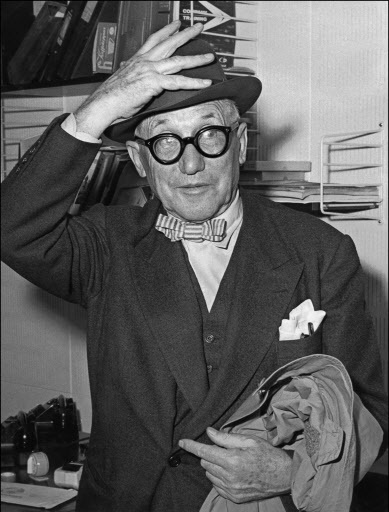

PARIS (AFP) -- Love him or loathe him, few people have changed the world we live in more than Le Corbusier, one of the fathers of modern architecture, whose works were placed Sunday on UNESCO's prestigious World Heritage List.

His ideas about utilitarian concrete buildings have altered the face of cities across the planet and have had an equally profound influence on urban planning.

From his modernist master planning of Chandigarh in northern India to Paris, which he dreamed of levelling to make way for his own more rational city, the Swiss-born designer was never afraid of thinking big.

He left his greatest mark on France, his adopted home, where no less than 10 of the 17 projects which UNESCO classified as world heritage sites are located.

From the La Cite Radieuse housing project in Marseille to the Dominican monastery of La Tourette near Lyon and La Villa Savoye near Paris, it is also where he left some of his greatest masterpieces.

His designs for functional apartment blocks surrounded by parks dominated France’s postwar urban planning until eight years after his death in 1965 when it became clear that many were depressing and anonymous, and blamed for urban alienation.

Vertical cities

“You have to put him in context,” said Vanessa Fernandez an expert at the Paris-Belleville School of Architecture. “He came from an incredible avant-garde in the 1930s” when building techniques had yet to catch up with architects’ ideas.

His ideas about utilitarian concrete buildings have altered the face of cities across the planet and have had an equally profound influence on urban planning.

From his modernist master planning of Chandigarh in northern India to Paris, which he dreamed of levelling to make way for his own more rational city, the Swiss-born designer was never afraid of thinking big.

He left his greatest mark on France, his adopted home, where no less than 10 of the 17 projects which UNESCO classified as world heritage sites are located.

From the La Cite Radieuse housing project in Marseille to the Dominican monastery of La Tourette near Lyon and La Villa Savoye near Paris, it is also where he left some of his greatest masterpieces.

His designs for functional apartment blocks surrounded by parks dominated France’s postwar urban planning until eight years after his death in 1965 when it became clear that many were depressing and anonymous, and blamed for urban alienation.

Vertical cities

“You have to put him in context,” said Vanessa Fernandez an expert at the Paris-Belleville School of Architecture. “He came from an incredible avant-garde in the 1930s” when building techniques had yet to catch up with architects’ ideas.

“After the war in the face of a baby boom and slum housing they had to build three million homes in 30 years.”

Some of his “vertical cities” were adored by their residents, particularly his Marseille block built in 1945.

When the Mediterranean city was made a European cultural capital three years ago, La Cite Radieuse was one of its most visited attractions.

Le Corbusier allowed light to bath the double-aspect duplexes with their open plan kitchens, then a design revolution.

Inside everything was planned to Le Corbusier’s own human scale he called the “modular,” based on his ideal man, who, added Fernandez, was “handsome, sporty and six foot tall.”

Out-and-out fascist

The image, in fact, of the perfect Aryan. For the architect was also “an out-and-out fascist,” Xavier de Jarcy, one of his biographers told AFP last year.

Another biographer, Francois Chaslin, said he was a longtime far-right supporter, who was “active for 20 years in groups with a very clear ideology.”

He said his anti-Semitic beliefs were “kept hidden” long after his death to protect his architectural legacy.

Soon after arriving in Paris in 1920 Le Corbusier hooked up with Pierre Winter, a doctor who headed France‘s Revolutionary Fascist Party, and worked with him to create the urban planning journal “Plans.” When it closed, they started another called “Prelude.”

Jarcy said that Le Corbusier wrote in support of Nazi anti-Semitism in “Plans” and in “Prelude” co-wrote “hateful editorials.”

His 1925 urban plan to flatten the historic center of Paris included razing the Marais, a district long home to the capital’s Jewish community.

In October 1940, after France had fallen to the Nazis, Le Corbusier wrote to his mother, “Hitler can crown his life with a great work: the planned lay-out of Europe.”

Writer Marc Perelmen, who has investigated the architect‘s ideas for more than three decades, said that Le Corbusiers’s political and architectural ideas “are viewed separately, whereas they are one and the same thing.”

Born in Switzerland in 1887 as Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris, the architect moved to Paris at 20 and adopted his maternal grandfather’s name to show that man was capable of reinventing itself.

That was certainly true of his own life.

Despite his links with the wartime collaborationist Vichy regime, when he drowned in the sea meters from his famously tiny cabin he had built for himself on the French Riviera, he was given a state funeral at the Louvre.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)